I recently read Practical Object Oriented Programming by Sandi Metz and want to share the ideas that stood out the most to me.

Don’t start design too early

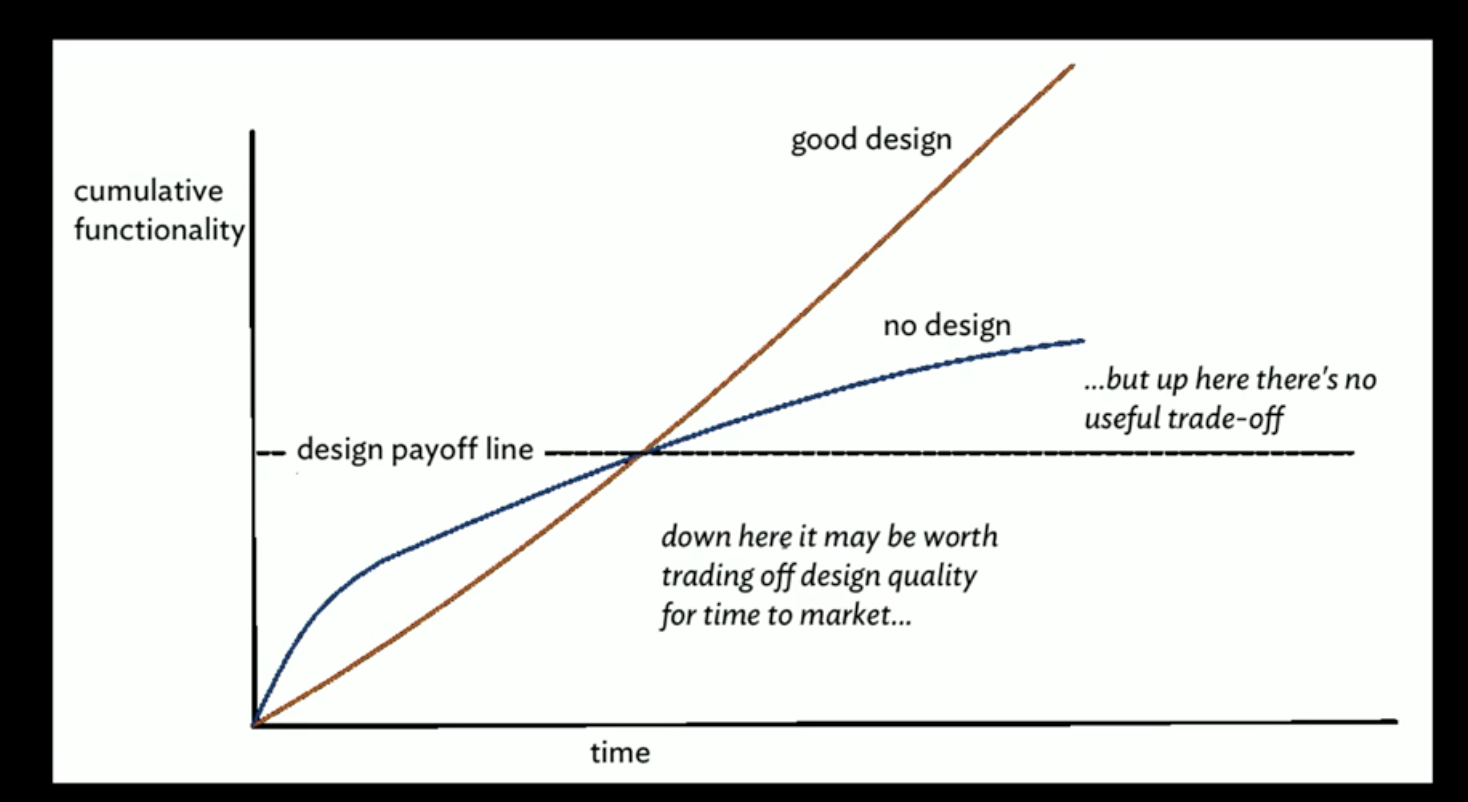

When do you know that your design is “good enough”? Well, it depends. If your code is understandable, usable, and you know it’s unlikely to change in the future, there is no need to “optimize” your design since there is no payoff.

You don’t need a lot of design early on. As you work on a file and see that it change more often, you want to start adding more design to make future changes easier.

If you start making design changes anticipating a future requirement this feature may get canceled and now you have a design that is no longer applicable and adds cognitive load ie (You’re not gonna need it)

Even if you have two plausible solutions or directions, you shouldn’t rush to decide until you are certain it’s the right move. You don’t want to make a decision early and have it be the wrong one. Wait until you have the information you need to make the correct decision.

That being said, this doesn’t mean you never refactor your code or avoid design principles altogether. Bad design will also make your life harder. Instead, use your judgment and make small refactoring that makes the code easier to work with within the present even if you don’t know what the future holds. But once the code is usable understandable, avoid over-engineering and adding design when you don’t need it.

Good design is about managing dependencies

When your classes have a lot of dependencies between each other it makes the code harder to change in the future. If a class depends on another object too much, every time that object changes, you’re class will have to change as well. The consequence is that when you want to make a small change to how a class behaves you will have to change a lot of things in other seemingly unrelated classes. This in turn increases the chances of introducing small bugs to your program.

Furthermore, the more interrelated objects are with each other, the harder they are to reuse in new contexts. If an object knows too much about the context it’s being used in, it will always only be able to be used in that context. If you want to reuse it in a different place, you might find yourself duplicating certain parts of the code into a new class.

Good design can help you avoid these two issues by providing you with patterns that reduce the dependencies in your code or otherwise manage the dependencies you do have so that the class remains small, easy to use, etc.

For example, you can apply principles such as single responsibility principle]], dependency injection, law of demeter, etc.

Focus on messages not classes

Object Oriented Programming isn’t about the objects themselves but the messages the objects send to each other. Instead of focusing on which objects you need in your code, think about the type of messages you need to send, who should send them, and to whom, and your domain objects will be created from there.

If you focus on classes, you may try to add messages to your existing set of classes even if it doesn’t entirely make sense for a class to respond to this message.

The first step of design should be “I need to send this message, who should respond to it?” Let the answer inform which classes you need to create. You may even discover new domain objects you were not aware you needed.

Duck Types

Duck types are a name for objects that share a public interface that cuts across classes instead of being restricted to one type. In this way, duck types are related by their behavior more so than their type. For example, schedulable objects may all implement the schedule method even if they don’t share a schedule type. Sometimes, all duck types share is the name of the methods they all implement. However, they all may share behavior as well, that may be defined in a module.

How to find a duck type

Whenever you have code that takes a parameter and then checks the class of the objects or call responds_to? on the object to decide which method to send to the object, you have a hidden duck type. These objects may not be the same type – but they do need to share some behavior (since they are being passed to this method for a reason).

For example, you have a trip that takes a mechanic or driver:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

class Trip

def prepare(preparer)

if prepare.is_a(Driver)

preparer.buy_food

else if prepare.is_a(Mechanic)

preparer,prepare_bicycles

...

end

end

Here you have a Preparer duck type between Driver and Mechanic where they both need to prepare trips. If you update them to share an interface for prepare, this code will be simplified. It will be easy to add new Preparers without modifying the trip to check its type.

1

2

3

4

5

6

class Trip

def prepare(preparer)

preparer.prepare_trip

end

end

The reason why duck types get hidden is when we focus too much on concrete class. We see that an object does not respond to a message and go looking for a message it does respond to. If we focus on messages, not classes when designing code, then we can see that all of these objects need to respond to the same message and can uncover the duck type.